By Kevin Sheives

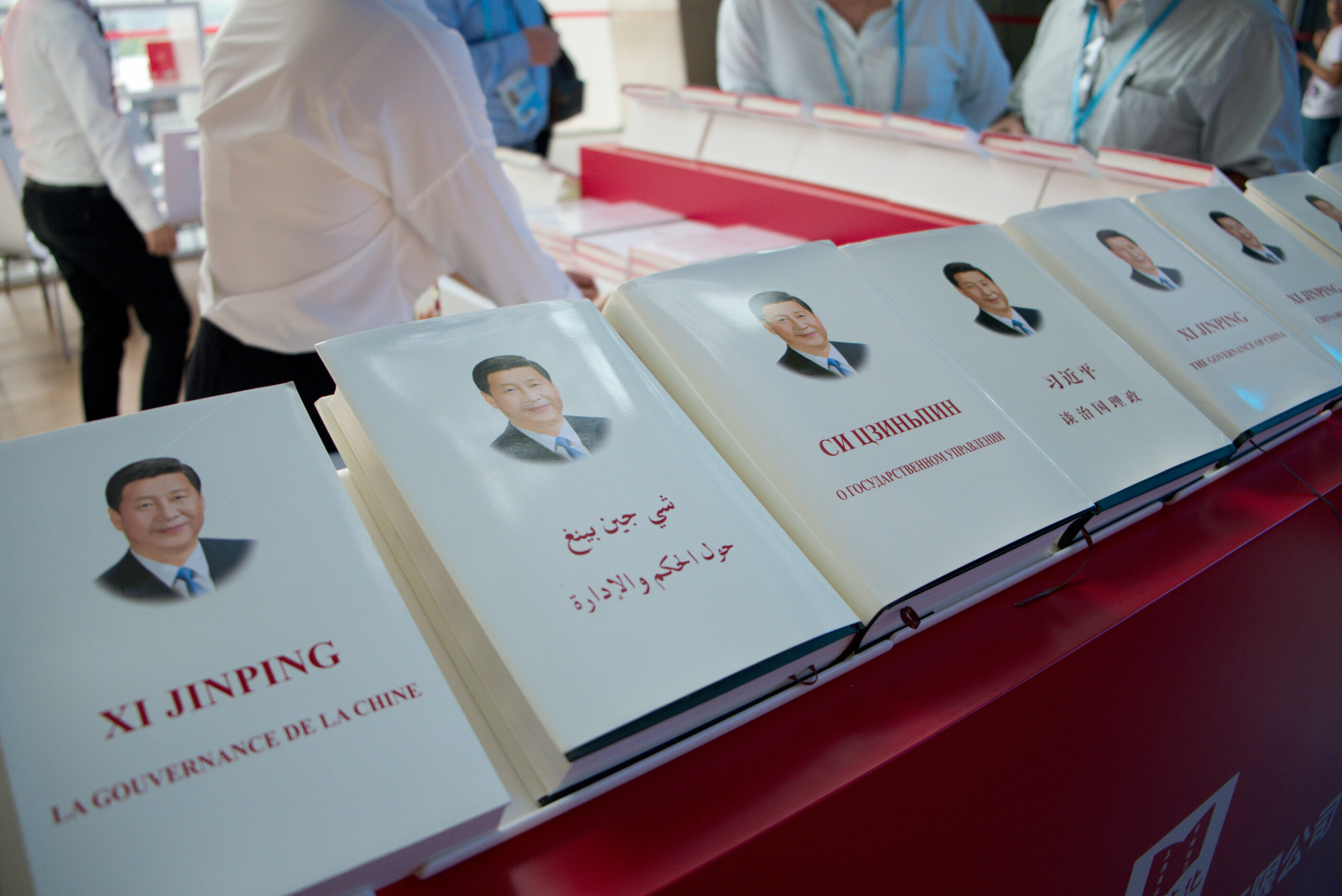

China isn’t just the CCP’s China; it is now Xi Jinping’s China. At China’s 20th Party Congress last month, Xi Jinping broke the precedent set by recent Chinese Communist Party (CCP) predecessors and extended his various leadership roles in the Party another five years and perhaps indefinitely. He packed the seven-member Politburo Standing Committee with loyalists and declined (again) to imply a successor. The emphasis was on fealty to Xi, rather than a more meritocratic approach to personnel that his predecessors had begun to institute. Representatives of a more moderate, technocratic CCP faction led by former General Secretary Hu Jintao were removed from the Party’s governing council, the Central Committee.

The Party Congress was another setback for the rights and freedoms owed to the Chinese people, who have been forced by the Party to accept a false choice between economic growth and authoritarian rule. China’s Era of Reform and Opening appears to be completely over. The protests that have erupted throughout Chinese society over November is part proof that the Chinese people want and deserve better than oppressive Party rule. Xi’s deeper consolidation of power, however, also portends a more ideologically-driven and rigid approach to international engagement by China—one that is increasingly controlled by Xi’s own imperatives. Unfortunately, Xi’s moves follow a well-trodden global pattern set by other dictators.

“The Party Leads All” under “Chairman-of-Everything” Xi

With some exceptions, the world’s engagement with China during the last seventy-plus years of CCP rule has been, in reality, engagement with the Party. China’s engagement in global economics, diplomacy, people-to-people exchanges, and media have all been heavily influenced, and in some cases directed by, CCP. This trend of Party control over the Chinese state and society has been placed in overdrive under Xi.

Five years ago at the 19th Party Congress, Xi changed the CCP Constitution, pushing China further back toward Mao-era ideology: “Party, government, military, civilian, and academic, east, west, south, north, and center, the Party leads everything.” Since 2017, Party cells have ordered to be established within state-owned, private, and even foreign businesses in China. Xi’s signature foreign policy strategy, the Belt and Road Initiative, (BRI) has metastasized into one exporting not just Chinese capital and labor, but also CCP ideology, political party training, and “proper management” of non-government organizational activity. China’s surveillance state, perfected in the dystopian East Turkistan/Xinjiang and Tibet regions, has been exported to democratic and authoritarian states alike.

Now, as Xi has fully consolidated his singular control within the CCP and put aside its decades-long collective leadership model, his recent integration of authoritarian ideology into China’s foreign engagement strategies will deepen. At its root, the prioritization of ideology over more pragmatic methods of leadership is grounded in insecurity. Highly personalized ideological adherence to precepts like Xi Jinping Thought, nationalism that attempts to paper over foreign policy contradictions like China’s South China Sea policy, and the heaping of blame on “foreign forces” to explain domestic political opposition to the CCP’s rules have all been accelerated by Xi. In 2018 as Xi’s plan for consolidation began to materialize after the 19th Party Congress, Susan Shirk wrote in the Journal of Democracy that “[Xi’s] insecurity is glaring…the overriding concerns [of the Party] are to reinforce Xi’s authority and keep the Party in line behind Xi.” In the 20th Party Congress “work report” that guides China’s domestic and foreign policy, “security” was referenced 91 times in one way or another—a huge leap from the 54 references in the previous work report. (The CCP work reports rarely offer that much variation from year to year.)

Xi’s personal management of the Chinese Party-state and institution of new national security bodies has even given him the nickname “Chairman of Everything.” When autocratic leaders and dictators feel insecure, they often tighten—not loosen—their grip on society and their country’s foreign policy levers.

Dictators Operate Differently than Democrats

If the past decade of China’s sharp power activities is precedent, how should we interpret this month’s events at the Party Congress? With China and the CCP beholden to one individual’s preferences, what does this mean for China’s global influence strategies?

This question is difficult to answer. The Party’s opacity makes prognostication a difficult task, but a few assumptions could be made based on the traditional pattern of dictators.

Internationally, dictators represent themselves and their power base, not necessarily their country’s interests or the sum of its parts. These days, autocrats are finding ways to cooperate and maintain their grip on power at home and abroad; and they applaud each other in the process. When the Party Congress concluded, leaders from autocracies and even some democracies responded with over-the-top congratulatory messages. One leader singled out Xi’s “unwavering devotion to the Chinese people”— a laughable message in the face of widespread oppression of so many in China. The same praise that Party loyalists are expected to heap upon Xi at home may now become an expectation for many of China’s partners.

At the 20th Party Congress, Xi chose to elevate diplomats known to be strident in their defense of Xi and the primacy of the Party, both privately and in China’s international propaganda apparatus. Former MFA spokesperson Qin Gang was elevated to the 205-member Central Committee, and FM Wang Yi made it onto the 27-member Politburo. Qin Gang had struck a more adversarial tone than his predecessor as U.S. Ambassador in recent years. A trend I saw personally in meetings during my career at the U.S. Department of State, Wang Yi evolved over the last two decades from a skilled, smooth negotiator to an itinerant defender of any perceived complaint about China’s foreign policy. As foreign minister, he publicly pushed the foreign ministry to renew its “fighting spirit” (a refrain of Xi’s speech) in defense of China and Xi’s management of the country.

Authoritarian regimes, especially those defined by personality cults like that which Xi has purposefully developed, are often rigid and unable to self-correct poor decisions that elections and compromise naturally produce in democratic power transitions. China’s long-held strict adherence to a zero-Covid policy is one such example—and a topic the International Forum has researched extensively. Amid the draconian lockdowns and surveillance systems that China’s health authorities instituted, especially in Shanghai, dissent has broken out among Chinese citizens. Throughout the November protests, occasional dissent has now transitioned into more widespread demonstrations and protests. China’s economy continues to suffer from the resulting supply chain shortages. Yet these policies remain unquestioned for far longer than the rest of the world. What was the reward for Li Qiang, the Shanghai Party Secretary responsible for maintaining this harsh posture? The number-two slot on the Politburo Standing Committee, second only to Xi himself. The expectations of personal praise and occasional kowtowing by foreign leaders receiving China’s COVID-19 aid (masks and vaccines)—partly designed to applaud Xi’s management of the crisis—could become even more commonplace internationally in other areas of global engagement with China.

Rigidity could also become an even more prominent feature of China’s domestic and foreign policies. For example, Xi has made the BRI his signature international initiative. In a regime defined by personalistic rule, failure is not an option lest policy implementers run afoul of the unquestionable leader’s directives. Chinese entities involved in the BRI (embassies, state-owned enterprises, policy bank lenders, or private individuals and businesses) could be unable to make adjustments demanded by local actors such as greater environmental sustainability, use of local labor, or debt renegotiation. With China unable to adjust its engagement strategies, local actors must find innovative ways to adapt that engagement to their local interests.

Dictators often project an inflated view of their own power and that of their country. While all democratic or autocratic leaders highlight (or boast of) their successes, authoritarian systems lack the capacity for alternative narratives to surface about a country’s direction. Autocrats want the world to see them as strong and incapable of weakness, when in reality their weaknesses are often disguised and hidden by the regime’s strict control of their own information environment. In democracies, opposition politicians and civil society representatives in the media and elsewhere serve as a check on these bloated narratives.

For example, in Xi’s speech on the Party Congress work report, Xi claimed that “China’s international influence, appeal, and power to shape have risen markedly.” However, according to polling by the Pew Research Center, the past five years of “Wolf Warrior diplomacy” by China’s diplomats, international concern over China’s human rights and technology policies, and a variety of failed investment and labor practices in certain countries has produced a massive decline in positive views of China. In the face of these declines in its soft power appeal, China has struggled to adapt its diplomatic and international engagement strategies. It’s difficult to see the Party-state being able to adjust to these failures under Xi.

The 20th Party Congress was not just a coronation of Xi Jinping, but also a coronation of his ideology and rigid methods of governing. Within China, the Party uses a mix of incentives to induce cooperation, eliminate dissent, and demand expectations of unquestioned support from the Chinese population to maintain its hold on power. Like other dictators, those same expectations that Xi expects from the Chinese people are likely to become those he places on the rest of the world.

Kevin Sheives is the deputy director of the National Endowment for Democracy’s International Forum for Democratic Studies. Follow him on Twitter @KSheives.

The views expressed in this post represent the opinions and analysis of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for Democracy or its staff. Image Credit: Artwell/Shutterstock.com.