By Susan Shirk

China in the twenty-first century is a vibrant modern economy and society open to the world, with a large and well-educated urban middle class. Many people inside and outside the country expected its political system to follow the historical example of other authoritarian regimes by gradually institutionalizing governance to make it more accountable, responsive, and law-bound.

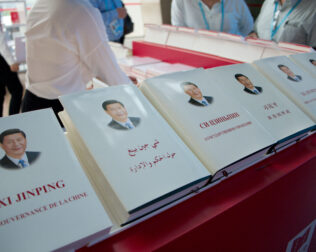

Until 2012, that is essentially what happened. But under Xi Jinping, China is making a U-turn. Personalistic rule is back and with it the risk of arbitrary decision making that often results from the excessive concentration of power, as Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping warned after Mao Zedong’s death. The risk to China and to the world of a personalistic regime in Beijing is particularly acute today when constraints on Xi in the global arena are weakening.

Why is the CCP heading back to personalistic rule after more than thirty years of institutionalized collective leadership? The following six factors have foiled plans to prevent the overconcentration of authority and the rules governing leadership competition:

1) The rules concerning the CCP general secretary’s retirement are unwritten. Written rules specify retirement ages for government, military, and Party officials at various levels and mandate universal term limits. Yet the rules governing leadership turnover at the apex of power within the Party are unwritten. Neither the CCP constitution nor any other document fixes retirement ages or term limits for members of the Central Committee, Politburo, and Politburo Standing Committee, or for the general secretary himself. And now that Xi has engineered the abolition of the presidential term limits in the state constitution, there is no written rule stopping him from ruling for life.

2) Retired leaders still exercise informal influence. Under term limits, the informal dynamics between the retired and current top leaders, as well as between the current leader and his successor-in-training, helped to check dictatorial tendencies and ease the sharing of power and patronage within the elite. But today, Xi Jinping’s predecessors are too old or cowed to constrain Xi Jinping, nor is there a preappointed successor with whom Xi must share the elite’s loyalty.

3) The Tiananmen crisis exerts a lingering effect. In 1989, the CCP’s leaders were split on how to respond to demonstrators protesting inflation and corruption. After the military crackdown, influential CCP figures including retired leaders blamed the close call on the Party’s having given up too much control through ill-advised delegation and decentralization. The authorities reversed the separation of the work of government agencies from the Party that had reached a high point in 1987, when a constitutional change eliminated CCP groups within ministries. This reversal smoothed the way for the CCP under Xi to reclaim policy-making authority from the government State Council.

4) There is no enforcement outside the Chinese Communist Party. Even as he was working to make the CCP and its rule more institutional, Deng Xiaoping had a line he would not cross: “No Western-style separation of powers.” This aversion to giving the legislature or courts authority to check the power of the CCP or its leader meant that the institutionalization project from its outset had a built-in limit.

5) Communist parties have an “ambiguity of authority” problem. With no institution outside the CCP able to check the behavior of Party leaders, this duty falls to the collective institutions of the Party, in particular the Central Committee. However, its ability to stop a CCP leader from ruling dictatorially or making policy misjudgments is limited by the fact that all Central Committee members hold their positions as state, Party or military officials at the pleasure of the top Party leaders, as well as by its unwieldy processes (it lacks a committee structure) and infrequent meetings.

6) There were failures of collective leadership under Hu Jintao. Hu comes in for much criticism within China as a weak figure who never fully escaped Jiang Zemin’s continuing interference. The problem was not so much indecisiveness as a failure to rein in the parochial interest groups within the Party, the government, and the military. The most conspicuous failure of the Hu era was the massive corruption that this decentralized system allowed high-ranking politicians and military officers to get away with. Official corruption angered the public, which enthusiastically welcomed Xi’s determination to end the dishonest dealings of both “tigers” and “flies.”

Implications of Xi’s Personalized Rule

Xi is almost competely unfettered domestically; he has grasped all the levers of power and surrounded himself with sycophants. His signature projects, including the set of hugely ambitious infrastructure projects known as the Belt and Road Initiative, are going forward in the style of Mao-era ideological campaigns—officials vie to show loyalty by pressing eagerly ahead with whatever scheme the leader happens to favor.

In the world arena, meanwhile, Xi’s explicit ideological and mercantilist challenge to market democracies are forms of overreaching that are triggering Cold War-type reactions from other countries. What is more, arbitrary and imprudent decisions taken during a crisis involving the East or South China Seas, the Korean Peninsula, or Taiwan could escalate into a hot war. The risks posed by Xi’s overconcentrated power are not confined within China’s borders, but extend to the world beyond.

This post is based upon a longer article, “China in Xi’s ‘New Era’: The Return to Personalistic Rule,” that appears in the April 2018 issue of the Journal of Democracy.

Susan L. Shirk is research professor in the School of Global Policy and Strategy at the University of California, San Diego, where she chairs the 21st Century China Center. Follow her on Twitter @susanshirk1.

The views expressed in this post represent the opinions and analysis of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for Democracy or its staff.

Image Credit: yavyav/Shutterstock

Comments

“China in Xi’s New Era”: International Forum for Democratic Studies June 2018 Newsletter – NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR DEMOCRACY

June 13, 2018

[…] “Turning Back: China’s Governance U-Turn under Xi Jinping” by Susan Shirk. […]