By Rachelle Faust

The torch was lit, and a warning delivered: “Any behavior that is against the Olympic spirit—especially against Chinese laws or regulations—are also subject to certain punishment,” cautioned a Beijing Organizing Committee official during a January news conference. As athletes, journalists, and government officials participate in the 2022 Winter Olympics, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has leveraged a toolkit refined in the fourteen years since it last hosted the Olympic Games to manipulate the political landscape and stifle independent expression. Despite pushback from nongovernmental organizations and diplomatic boycotts prompted by high-profile controversies—such as the safety and sudden retirement of Chinese tennis player Peng Shuai, surveillance and censorship of foreign athletes, and China’s systematic human rights abuses in Xinjiang, Tibet, and beyond—the Games have carried on, along with Beijing’s authoritarian ambitions. The silence on these issues from the International Olympic Committee and corporate sponsors from democratic countries has been deafening.

However, China’s approach illustrates a pattern occurring beyond the spotlight of the Olympic Games: China, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and other illiberal regimes are increasingly drawing upon their domestic information manipulation and censorship methods for application to foreign markets. As these authoritarians’ efforts to coopt foreign partners, marginalize and intimidate dissenters, and control global discourses grow in scope and scale, private sector firms and even powerful multinationals face mounting pressure from autocratic governments to advance their preferred narratives and political agendas in settings beyond their domestic borders.

Authoritarian Censorship in Practice: China’s Pressure on Foreign Companies

The CCP employs a combination of political and economic incentives to signal to foreign companies that their operations will be jeopardized if they assist, do business with, or refrain from censoring voices and information designated politically undesirable. Even as human rights organizations cautioned private companies of the reputational risks associated with remaining silent about the CCP’s human rights abuses, many of the Games’ primary corporate sponsors declined to comment when asked about their role in either whitewashing or ignoring the Communist Party’s repression. Others have reversed course on their own public statements to satisfy CCP demands. American technology firm Intel, for example, apologized on its Chinese social media accounts after receiving strong backlash from the Global Times, a nationalist tabloid owned by the CCP’s official newspaper. Intel had previously instructed its suppliers to refrain from sourcing products or labor from the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

This pattern of reticence has emerged from businesses operating in diverse sectors ranging from technology to travel, and from entertainment to apparel. After Chinese sponsors and broadcasting partners cut ties with the National Basketball Association (NBA) in 2019, sports broadcaster ESPN mandated that coverage on its network avoid discussion of protests in Hong Kong. Multiple airlines, concerned about maintaining access to the world’s second-largest aviation market, conceded to a mandate from Beijing to change references on their websites and marketing materials that listed Taiwan as a “country” along with other global destinations. Consumer boycotts within China, fueled by CCP propaganda, have taken a toll on the bottom line of foreign companies that critique the CCP or take a public stance on China’s human rights abuses.

Censorship Across Borders

As foreign firms increasingly comply with local regulations in authoritarian countries that affect freedom of expression, a concerning pattern has emerged: domestic censorship can easily extend beyond a country’s borders. In compliance with Chinese regulations, video conferencing platform Zoom suspended the accounts of human rights activists who hosted online events related to the political crisis in Hong Kong and the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre, even though the account owners were based outside China. (The company later reinstated the users’ accounts and committed to no longer allowing requests from the Chinese government to affect users outside mainland China after facing public criticism.) Apple, meanwhile, adapted a list of censored keywords originally developed for its product personalization service in mainland China for application to users based in Hong Kong and Taiwan. Though it is unclear whether the overlap in censored terms was intentional to appease Chinese authorities or the result of simple negligence, researchers warned about increasing compliance with censorship demands as the cost of doing business in China. LinkedIn cited local Chinese laws as justification for blocking international user profiles and posts within China before later shutting down its social media service altogether in the country. French video game company Ubisoft similarly planned to accommodate the CCP’s preferences on graphic violence and sexual imagery in a universal version of its game “Rainbow Six Siege” before fan backlash caused the company to reverse course.

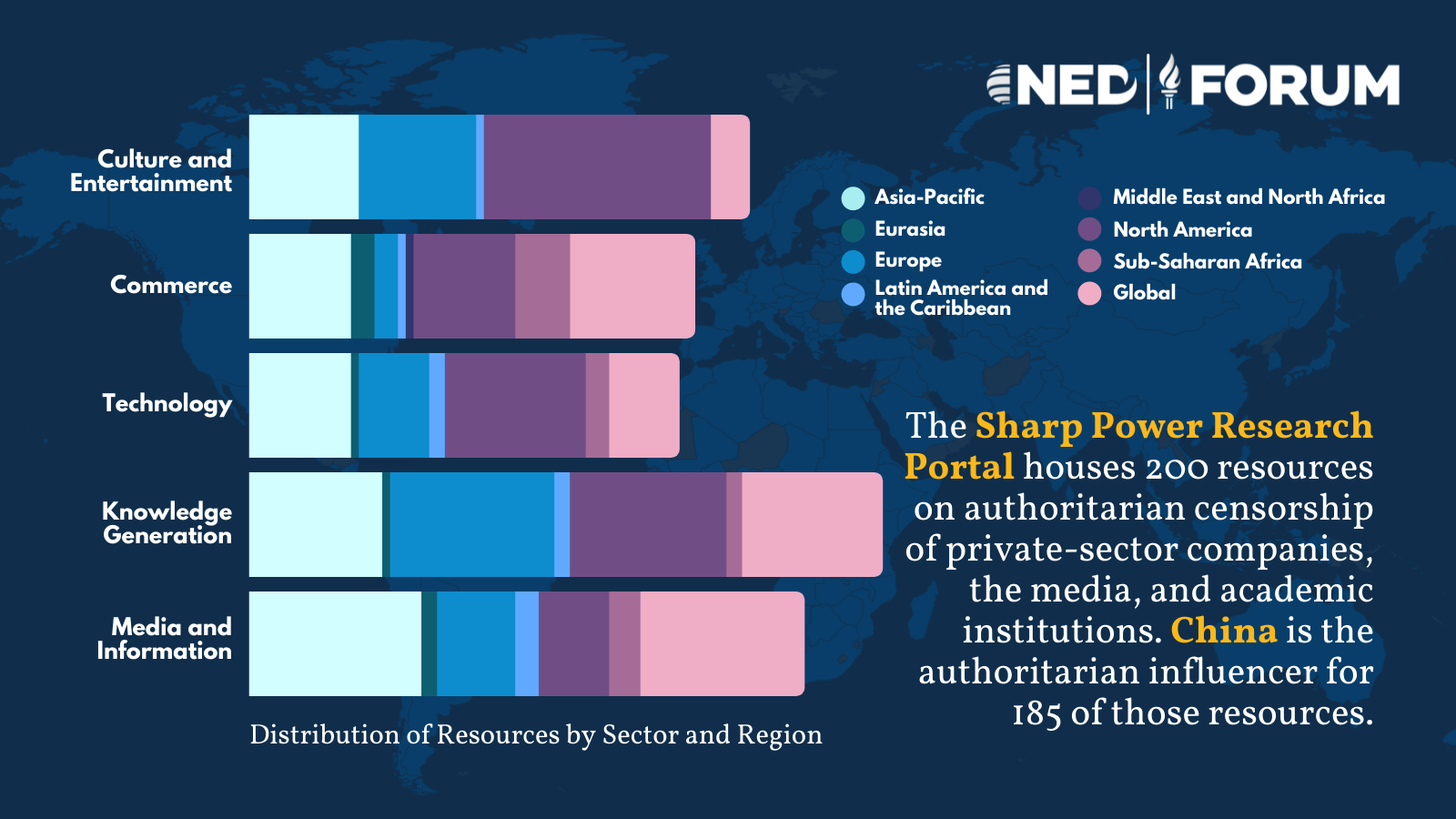

As the world’s second largest economy, China possesses a unique ability to induce censorship within various industries across the global private sector. But it is not the only illiberal actor to do so. Russia and Saudi Arabia, among other authoritarian regimes, are leveraging similar tactics—including official legislation, fines, personal intimidation, and threats of throttling the internet—to push foreign companies to take down or alter content and censor search results. In 2019, for example, Apple bowed to pressure from the Kremlin and altered some maps-based apps to depict Crimea as part of the Russian Federation for users based in Russia. In the entertainment sector, Saudi Arabia leveraged the kingdom’s cybercrime law to implore Netflix to remove an episode of a comedy show that criticized Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. The wide-ranging effects of foreign censorship on private companies and institutions is well documented in the Sharp Power Research Portal.

The Stakes of Foreign Censorship

The extraordinary foreign commercial relationships that open societies have forged with authoritarian countries, China first among them, have enabled new channels for authoritarian control to limit expression in democratic societies. For foreign companies facing the prospects of official reprimand, legal troubles, consumer backlash, and financial risk, compliance with authoritarian censorship demands can sometimes outweigh the reputational benefits of enabling free speech and generating products that facilitate creative expression. Perhaps most concerning, anticipatory self-censorship is becoming the norm for firms seeking to appease authoritarian censors like China. To maintain access to authoritarian markets, as well as audiences based in authoritarian settings, companies are becoming circumspect about controversial subjects or electing to avoid them all together, without explicit pressure from authoritarian influencers. As technology firms, publishers, video game companies, and other private corporations privilege authoritarian narratives, illiberal regimes will become emboldened in their efforts to shape global discourses and set new expectations.

Rachelle Faust is an assistant program officer for the International Forum for Democratic Studies at the National Endowment for Democracy.

The views expressed in this post represent the opinions and analysis of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for Democracy or its staff.

Image Credit: Kachor Valentyna / Shutterstock.com