By Sarah Cook

In just the past month, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) added to its long track record of foreign influence. New details have emerged about the PRC’s continued involvement in espionage, hacking, security cooperation, media information manipulation, and political interference among other activities.

Taiwanese chipmakers have been targeted with espionage that funnels key technological know-how to the People’s Republic of China (PRC), even as a former presidential staffer faces jail time for spying on Beijing’s behalf. An ex-aide to a German lawmaker was also convicted of espionage for China, carried out over the course of 20 years. A security report revealed a sophisticated China-linked hacking operation targeting the United States, complete with spearphishing that impersonated a prominent lawmaker shaping America’s China policy. And a detailed NATO report outlined how information manipulation campaigns emanating from China and directed against members of the alliance are “spreading further and faster than ever before.”

Yet, while telling, these revelations do not capture the full scope and scale of PRC foreign influence efforts, nor the variations in how those efforts play out across different countries and sectors. While criminal investigators and cybersecurity researchers expose the misdeeds of spies and hackers, subtler CCP inroads are eroding democratic institutions and strengthening Beijing’s ability to impact decision-making around the globe.

That is where projects like the China Index, published by the Taiwan-based non-profit DoubleThink Lab last month, are immensely valuable. The latest edition of the Index assesses and ranks PRC influence in 101 countries across nine domains: Academia, Domestic Politics, Economy, Foreign Policy, Law Enforcement, Media, Military, Society, and Technology. (Doublethink Lab defines PRC Influence as “the power to affect the decisions of other countries so that they align with the cultural, diplomatic, economic, military, political, or social interests of the PRC.”)

This massive project draws on input from international experts and local researchers worldwide. The full report and dataset are worth exploring, but here are four key trends that stood out.

1. 70% of Countries Experienced a Rise in PRC Influence

The finding that PRC influence is increasing globally won’t surprise those tracking this issue, but the Index’s bottom-up, systematic data validates impressions among China watchers and helps measure the wealth of research on the CCP’s foreign influence activities. Of the 81 countries included in both the 2022 and 2024 editions, 56 saw higher overall influence scores in 2024, while only 24 declined (one remained unchanged). That’s nearly 70% of the original countries experiencing a measurable rise in CCP-driven influence over two years, often across multiple domains.

The China Index utilizes relative rankings (ranking every country covered on a list that runs from highest to lowest levels of PRC influence). Many countries that fell to a lower relative position on the Index still experienced increased PRC influence since 2022. The United States, for instance, saw increases in eight of nine domains—most notably in Society and Academia—despite dropping 17 slots to #38.

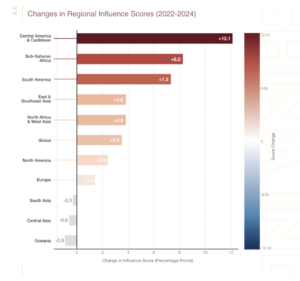

2. The Global South Is a Top PRC Focus for Influence, With Growing Attention to Latin America

As I noted in another recent article, Beijing is prioritizing the Global South, especially outside Asia, and arguably gaining more traction there than in the United States, Europe, or Australia. The China Index findings confirm this trend. Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America (South America, Central America, and the Caribbean) recorded notable increases in average influence scores, with Central America and the Caribbean showing the largest jump of any region, by far. This may reflect Beijing’s relatively recent focus on the region, and the the extent of the PRC’s influence activities there. Beijing is now extending to this region the kinds of inroads it had previously built up through more longstanding involvement in settings like Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Average PRC influence scores in Central America and the Caribbean increased by the largest margin of any region. Credit: China Index.

Specific country trajectories also underscore this focus on the Global South. For example, Nigeria climbed 10 places to #4 and now ranks as the top non-Asian country (behind Pakistan, Cambodia, and Singapore). South Africa joined the top 10, while Chile surged 22 slots to #8. Panama and Argentina rose 11 and 20 spots, respectively. Many of the countries that saw the largest China Index ranking jumps from 2022 to 2024 also scored High or Very High in Freedom House’s 2022 Beijing’s Global Media Influence study.

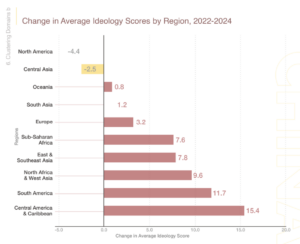

3. Beijing Is Exporting its Ideological Influence More Rapidly through Civil Society and Media Engagement

The Index groups its nine domains into three buckets, with the “ideological” category covering influence over Media, Academia, and Society. The 2024 edition found expansion in these ideological domains across 58 countries. This growth is “targeted rather than uniform, with notable gains in regions where PRC soft power initiatives had previously been less prominent,” suggesting Beijing tailors its efforts to exploit new opportunities.

Exerting ideological influence was a major focus for Beijing and its proxies, especially in Latin America and elsewhere in the Global South. Credit: China Index.

Several data points stand out:

- First, the reach of grassroots engagement through Chinese diaspora cultural events—often linked to the United Front Work Department (UFWD) or PRC diplomats—nearly doubled, from 37.5% to 72.3% of countries.

- Second, PRC entities now control or hold major stakes in at least one top-five social media or messaging app in 66 countries, up from 36, a trend driven almost exclusively by the popularity of TikTok.

- Third, looking at traditional media, 51 countries had journalists or media organizations tied to CCP-backed networks like the Belt and Road News Alliance, and 75 saw journalists or influencers participating in PRC-organized travel. Similarly, 76 countries had media outlets delivering Chinese state-funded content or committed to content-sharing agreements with PRC state media—an increase from 2022.

This expansion of societal and media influence tactics—effective at shaping public and elite opinion to induce “policy alignment” with the CCP—correlates with an apparent shift away from overt coercion after diplomats faced local backlash. While more assertive threats and pressure campaigns persist, the findings suggest Beijing is favoring subtler, broader, and more long-term tactics that aim to reshape its political environment.

4. Increased Law Enforcement Collaboration with the PRC Threatens Freedom and Sovereignty

One disturbing finding is Beijing’s growing influence in the Law Enforcement domain, which includes extradition treaties, surveillance exports, training, and PRC-linked security service activities abroad. Seven of ten indicators showed that more countries increased their collaboration with PRC security forces. Given these agencies’ brutality against dissidents, activists, and religious believers at home, as well as the regime’s aggressive transnational repression targeting people abroad, this trend raises fundamental concerns. Beijing seeks legitimacy in the law enforcement space for political and economic gain, but cross-border cooperation poses human rights and national security risks that warrant greater scrutiny. No government should emulate the CCP’s abusive, intrusive tactics, nor serve as a vehicle for the regime in Beijing to globalize its repressive reach.

Coordinated Investments and Civic Responses by Democracies Are Needed

These takeaways only scratch the surface of the China Index’s findings. The trends outlined above have likely intensified in 2025 as Beijing capitalizes on cuts in U.S. funding to global media, democracy, and development assistance. Yet the implications extend beyond geopolitical rivalry. One reason so many people around the globe contribute to projects like the Index is because they see the negative impact of CCP influence manifesting in their own societies.

As this data fosters greater understanding of the risks of authoritarian expansion, hopefully it will spur discussions on how to strengthen democratic responses. Indeed, recent news stories like those cited at the opening of this piece highlight how regulatory probes, legal enforcement, and prosecutions can raise public and policymaker awareness of CCP tactics, adjust incentive structures, and potentially deter local actors who might collaborate with the PRC regime. At the same time, governments and private donors can help catalyze rights-respecting responses to these activities by supporting local civil society and media who can expose CCP influence efforts and help insulate democracies against their insidious effects. The nuanced insights offered by local voices, grounded in grassroots knowledge and observations, hold promise for responding to these worrying trends.

Coordinated investment on this front by a wide range of international actors is urgently needed to strengthen resilience, protect free expression, and enhance national security for democracies in this new, emerging world order.

Sarah Cook is an independent researcher and author of the UnderReported China newsletter, where an earlier version of this article first appeared. Read her past work with the Forum on China’s Global Media Footprint, available in both English and Spanish. You can find Sarah on X, Linkedin, and Bluesky.